Artist Conversations | Robert Weingarten: Palettes

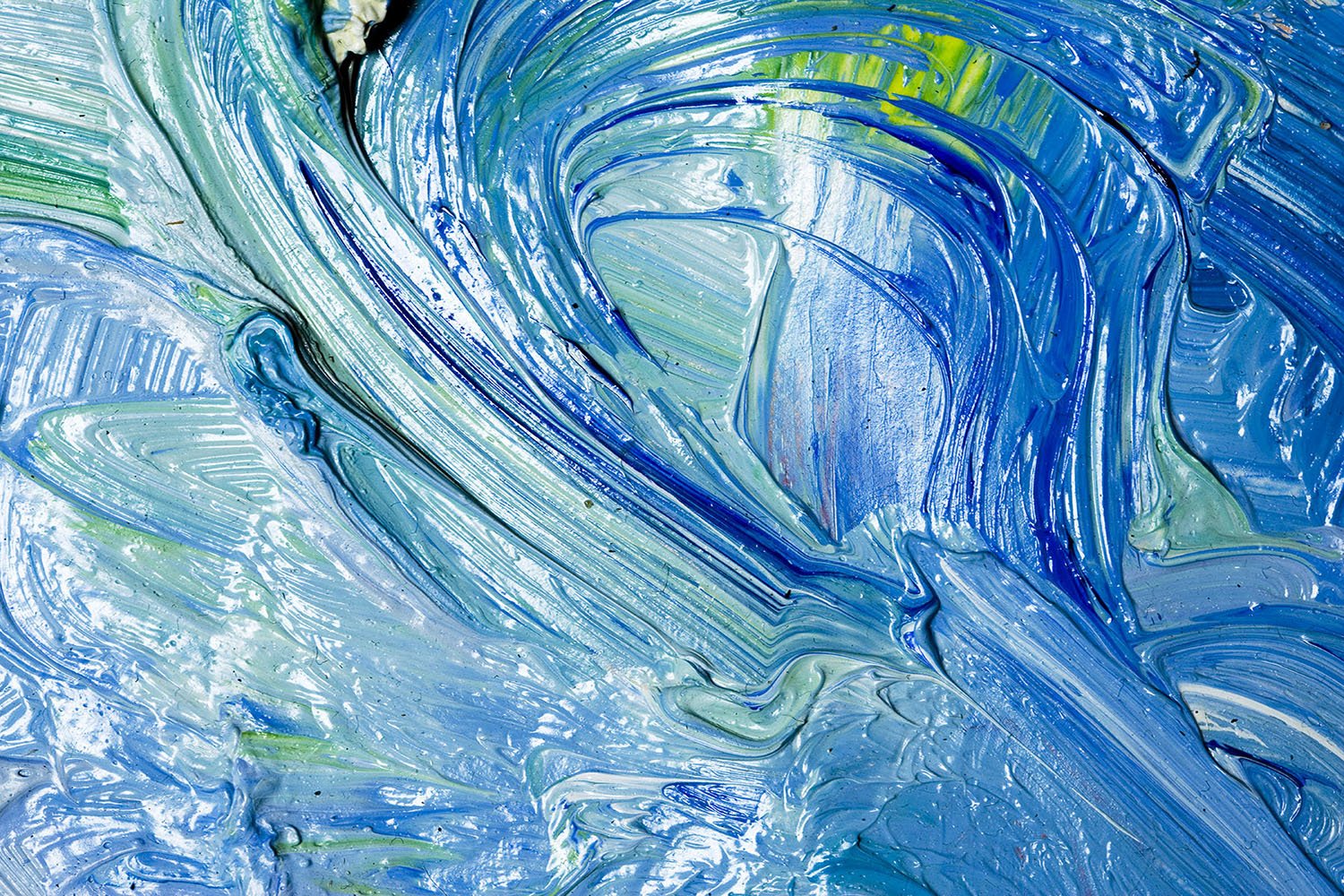

Displayed as large-scale photographs, Weingarten’s Palettes reveals the intimate moments with the tools of the most celebrated contemporary artists, applauding painting practice and technology as the conduit for sensational visual experiences and inviting us to widen our collective lens by zooming in to our everyday surroundings.

Now a traveling exhibition, Curatorial sat down with photographer Robert Weingarten to discuss the inception of his Palettes series, the evolution of his metaphorical portraits, and how painting has influenced his career in photography.

The Palettes exhibition is now available for booking. For exhibition details and booking information, visit our website.

Fig. 1 Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral, West Façade, 1894

Curatorial: You credit painting to be a major influence on your artistic career. Who were the first painters that caught your attention and why?

RW: What first caught my eye were the impressionists, with their focus on the use of color and light in painting (fig.1). The very first photographs I took were landscape and I borrowed the impressionist practice of exploring how light and color influenced the scene I was photographing. As my taste changed and matured, my interest moved toward modern and contemporary art and it was abstraction that became the main influence for the Palettes Series.

The idea behind the Palettes series derived from the initial tensions between painting and photography. The introduction of photography challenged painting’s status as the primary means of image-making. These tensions broke out even within photography, for instance the pictorialists who revered painterly compositions while Group f/64 argued for realism. The painting world finally realized that photography had the upper-hand in capturing real-life but that painting could create genuine abstraction. Through the Palettes series, I realized I could create abstraction from the raw materials of the greatest living painters.

Curatorial: Was there any scientific motivation behind Palettes?

RW: My main scientific motivation was in the 6:30am series which dealt with chromatic adaptation, how our eyes are informed by our minds. We see what we’re looking at through our history of gathered knowledge. For instance, we accept the ocean is blue and will accept variations on blue but not red. When I was photographing for the 6:30am series, I’d be looking at the ocean and see one thing and the film would capture something completely different since film is a pure rendering of the chroma, not influenced by the brain.

Palettes did not have a scientific background since it was grounded in abstraction. However, because I wanted to reflect the colors they were using and how they were using them, I did use a color meter measuring in kelvin and rendered the image to the data I extracted.

Fig. 2 Robert Weingarten, from 6:30am series #9, #13, #18, #77, #82, #85, #104, #105, #106

Curatorial: Do you consider the artist’s environment integral to his or her process of creation?

RW: I’ve always been interested in light, the color of light and how it affects our perception of things and our environment. The 6:30am series, for instance, was based on the color of light and how it fluctuates with atmospheric changes at the same place, the same exact time, over time.

This influenced my concept of Palettes. I wondered if the color palettes that are used by painters is a reflection of the environment in which they paint.

I started by asking the artists: “How does the quality of light that you work in affect the palette?” They had varying answers, none satisfactory. For instance, the lightest palette I photographed, all pastel and wonderful, was a on a dark winter day in Richard Estes studio. The darkest palette I photographed was on a clear, sunny day in an outdoor studio of Ed Moses’.

I learned that the palette had no relationship to color of light. As Eric Fischl best described it, “I believe there are two lights you live with: the light you see and your psychological light…I think that the latter is the one that informs my palette more than the former.”

Curatorial: Matthias Schaller’s Das Meisterstück (The Masterpiece) series asserts the painter’s palette as an accurate portrait of the artist. How does your Palettes series address this idea?

RW: For Palettes, I took to raw materials as the forefront, whatever raw materials I thought were integral to the artist’s process. In photographing only living artists, all of the artists were in the studio when I was photographing. It gave me an opportunity to ask them about the quality of light they worked in, the chromatic aspects of their palette.

I didn’t see it as a portrait of the artist but of course everything they touch is a portrait of themselves. In a sense you are analyzing how they work with their palette. Is it a bunch of stuff or are they working with fixed, controlled material? Do they work in a disorganized and crazed or a neat and sterile environment? Some of it shows, some of it doesn’t.

Fig. 3 Richard Estes, Holland Hotel, 1980 and Robert Weingarten, Richard Estes #1, 2005

Curatorial: How did your work on the Palettes series change your perception of the painter’s practice?

RW: It didn’t. It gave me more insight into the various ways they go about their work. Take Richard Estes (fig. 3) for example. His paintings are incredibly detailed, large-scale photo-realistic paintings. I would’ve thought that his reference photo would have been large too. I found the exact opposite: a very small photograph of the scene that he was painting, scotch taped to the upper right hand part of his easel. That amazed me!

Fig. 4 Wayne Thiebaud, Boston Cremes, 1962 and Robert Weingarten, Wayne Thiebaud #1, 2005

Curatorial: What is the difference between your Palettes series and those that you have separated as “artifacts” such as the depiction of Jim Dine’s brushes and stirring sticks, Al Held’s paint cans, and Wayne Thiebaud’s palette plates?

RW: The artifacts series came about naturally while onsite to photograph for Palettes. It was only in certain studios that something really appealed to me as a photographic, realistic shot.

For instance, the Wayne Thiebaud plates. His most famous works depicts these uniform plates of desserts with these certain, long shadows (fig.4). When I walked into his studio, I noticed his palette was a series of paper plates. It was amazing! So in addition to the abstract palette I did an Artifacts image of his plates. Essentially memorializing his methodology by making a Thiebaud of Thiebaud.

Curatorial: What has been most surprising in your artistic career?

RW: I guess that I had one. That’s the truth! And that I have one.

Robert Weingarten was born in 1941 and raised in New York City. Now based out of Los Angeles, Weingarten’s photographs have been included in over 100 exhibitions worldwide. His work is included in the permanent collections of more than 35 museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts | Houston, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the George Eastman House, and the National Gallery of Art. Previous projects include Earthscapes, Another America: The Amish, and 6:30 AM Series.